The main idea I want to get across today is that democracy, our government, our adherence to the rule of law hangs by a thread. It always has. What normally distinguishes America is that we all buy into the notion that the rule of law matters, that elections matter, and that the powers of government are constrained by the Constitution and those that enforce its words. When we all no longer agree and fail to buy into those notions, really bad things can happen.

On January 6, 2021, Donald Trump broke a tradition in American governance going all the way back to 1801. The 1/6 Insurrection is a black stain on America that damages our moral standing when it comes to democracy and government, the seeds of which Trump is sowing again as we head into the 2024 elections. The more people rehash the events of that day, of the mob, of the riot, of the storming of the Capitol and the Capitol Hill police working to hold the line, and the disgrace of Trump and everything he did (and didn’t do) that day, I feel a sickness in the pit of my stomach, and a revulsion. What Trump did was as unpatriotic and un-American as anything I had ever witnessed in my lifetime. Truly horrendous. If you do not feel ashamed of it, I feel sorry for you.

It didn’t have to be that way.

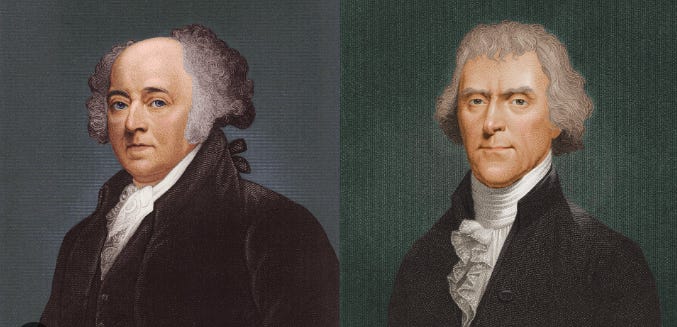

Our nation’s legacy of peaceful transfer dates back to our fourth election in 1800, when Federalist John Adams, loser of a spiteful, mudslinging election, lost to Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. Think I’m kidding about how hateful that election was? Here is a quick parody of modern campaign ads using actual words Adams and Jefferson said about each other regularly.

But Adams lost. And as the first losing President in American history, he had a choice. He still had all the levers of government at his disposal. He still was Commander in Chief of the military.1 Nothing, and I really mean NOTHING, stopped Adams from saying “I’m not going.” Never in the history of mankind has a power willingly, humbly and without force ceded that power to an adverse power by Rule of Law. History was even on his side.

But Adams wasn’t built that way. It wasn’t in his nature. He strongly, adamantly believed in the Rule of Law and opposed tyrants.2

The first transfer of power is one of the greatest milestones of any young democracy. It’s why so many of them fail. What separates the Banana Republics and the weak Democracies that crumble is a willingness and a faith to adhere to the Rule of Law, cede authority, and fight the good fight the next election cycle. Banana Republics and weak Democracies don’t do that; through mistrust, greed and arrogance, they devolve back to an authoritarian regime and backslide to tyranny.

Adams didn’t do that. He willingly handed the keys and the steering wheel of the country over to Jefferson. 3

However, this was all still new territory for our young nation. Everyone in government and working for government had been appointed by Washington and Adams; they were all Federalists. No doubt Jefferson would have wanted to fire them all if he could. Adams spent much of his last month in office trying to fill as many appointments as was possible. With the Federalists soon to be out of power, they passed the Judiciary Act of 1801 and made Adams Secretary of State John Marshall the new Chief Justice. Passage of the Judiciary Act also meant Adams could appoint more justices to lifetime appointments as well. Because party affiliation was relatively new and most of the people Adams appointed were not hard partisans, the Senate rubber stamped their approvals.

As the March Jefferson Inauguration deadline approached, the task was made to Marshall and several others4 to deliver many of the appointment papers to their respective nominees. On March 3, 1801, Adams’ last day in office, a mad scramble ensued to get as many to them as possible. Not all of them were delivered.5 When Jefferson took the Oath of Office the next day and saw undelivered commissions, he refused them and his Secretary of State, James Madison, refused to deliver them and they went about appointing their own people.

Another great moment in our nation’s young history arose. One of the undelivered commissions was to a man named William Marbury. He filed suit asking the court for a Writ of Mandamus to enforce Madison to deliver the appointment. With both a Federalist Supreme Court and a Democratic-Republican administration at odds, what was to stop Jefferson from ignoring the powers of whatever the Court said? What would prevent Jefferson from just saying “You know, I’m in charge now, and we’re doing things my way.” The Supreme Court, now led by John Marshall, was in a bit of a pickle; the further they went to enforce the commission, the less likely the foundations of our Constitution would hold.

So it was that when John Marshall decided the case, not only was he able to smack Jefferson around a little, but also ultimately side with the Jefferson administration on the matter giving Jefferson a win, while at the same time establishing the authority of the Judicial Branch of government, something that had been severely lacking until that point. The Court held that Madison’s refusal to deliver the commission was illegal, and that the appointment had been made when signed by the President (something Jefferson would have the ability to do on his way out the door too). But, he also held that the Court’s jurisdiction over types of cases like Marbury’s, which was through the Judiciary Act of 1789, exceeded the Court’s authority under the Constitution, and thus found that portion of the law unconstitutional, the first time in American history that had occured. This established the Supreme Court’s judicial review authority, the ability to consider laws and if they conflict with Constitutional Authority. Thus, Marshall gave Jefferson a win (he was not obligated to deliver the commission) and empowered our third branch of government to boot.6

The decision diffused a serious power showdown and proved the Rule of Law worked. It further confirmed that checks and balances on power are an important aspect of democracy, and the manner in which the Constitution itemizes out power held true. It strengthened all of our government, regardless of who was in those positions afterward. That is why these early decisions objectively made America and our democracy strong, particularly when it comes to the transfers of power.

And so it went that day. And every day since. With every PRESIDENT since. With ALL of them humbly respecting the Rule of Law and the powers they had in office. Every generation building on the last one, precedents continuously being added and agreed to, laws faithfully executed. For another 218 years…until.

All of that, Donald Trump chose to ignore and impose his own will on to dismantle on January 6th, 2021. He thought America was in fact nothing more than a Banana Republic or a weak Democracy. He thought he could be another Tin Pot Dictator. Many of his followers agreed. I was glad the structures of America held that day and the Constitution and Rule of Law still govern our nation. It might not have.

I am hopeful that those structures can hold again, but it takes effort and intelligence to maintain it. As Ben Franklin said, when asked what kind of government we’ll have outside the Constitutional Convention, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

What kind of nation will we have if Trump gets his way, either in court or in the coming elections? I don’t know, but I really don’t want to find out.

PurpleAmerica’s Recommended Stories

The title of this post comes from one of my favorite historical books, “What Kind of Nation: Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall and the Epic Struggle to Create the United States,” by Jeff Simon. It really put into perspective for me how tenuous this initial transfer of power from Adams to Jefferson was, and Marshall in his ultimate wisdom found a way to compromise and let Jefferson have a win, while at the same time establishing and empowering the third branch of government. I highly recommend it, as it is probably one of the most underappreciated moments in American History.

PurpleAmerica’s Cultural Corner

Because the transfer of power from Washington to Adams was cordial and less controversial, it largely doesn’t get the amount of attention that the one from Adams to Jefferson does, because that was a hostile transfer to an opposition party.

Nonetheless, the best (and funniest) reflection on that original transfer comes from Hamilton, where King George III first hears that Washington is stepping down…

Hard to believe Jonathan Groff is the same guy from Mindhunter.

PurpleAmerica’s Obscure Fact of the Day

This one is less obscure but still one of my favorite bits of trivia ever. Almost like assuring that the creation of our nation was even divine.

On July 4th, 1826, two co-signers of the Declaration of Independence who would eventually become deeply hateful rivals, Presidents, and reconciled friends, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both died. On the same day. Exactly 50 years TO THE DAY, the Declaration of Independence was signed.

Adams’ last words were supposedly “Jefferson still lives.” But Jefferson had died earlier that day.

PurpleAmerica’s Final Word on the Subject

Let’s give it to our nation’s Second President, John Adams.

LIKE WHAT YOU SEE? MAKE SURE TO SUBSCRIBE AND SHARE!!!

Footnotes and Fun Stuff

And as General George Washington had died previous the election, no other person had the same level of personal or military authority to contradict Adams if he so chose.

How much did Adams believe in the rule of law? When British soiders killed people at the Boston Massacre in 1775, not only did he defend the soldiers who he believed needed fair representation, he got them acquitted.

I was originally going to add “…and said ‘Good luck.’” but Adams didn’t do that. In fact, the campaign so embittered the two that they did not talk again until Adams reached out by letter to Jefferson in 1813, as the only living ex-Presidents ever.

Including Marshall’s brother.

It was said one of the most egregious offenders of not delivering the documents were by Marshall’s brother who would make frequent stops at taverns during the evening.

The way in which the opinion was written, Marshall applies the law and backslaps Jefferson repeatedly, saying he had to adhere to the law. But then he basically says, “But this part here is unconstitutional, so you’re OK.” [paraphrasing]. The order of this is very adverse to the way most cases are decided; first, you would have to approve the Court has authority, jurisdiction and is the right venue to hear the case and that the litigants have standing. This would be done BEFORE any decision was made on the merits of the matter. Marshall flipped that just so he could get some digs in at Jefferson first.