Part II: The Pilgrims Fail Upward

How Native Americans Saved 50 Puritans From Certain Death and in Repayment, They Threw a Party

This week, in recognition of Thanksgiving week, PurpleAmerica has a three part series on the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony. This allows us to write all these ahead of time and then just automatically push them out without having to do anything else. In fact, I’m writing this in September. At this moment, I’m probably gorging on some mashed potatoes and dark meat turkeylegs like Henry VIII while watching the Lions walk over their Thanksgiving Day opponent.

Now, most publications take one of two avenues with these wayward individuals; either they were essentially the founders of America in a certain way of speaking or genocidal relgious fanatics bent on destroying Native American culture. Neither of these depictions are true. And that is the focus of our week. We are going to demonstrate for you, our humble readers, just how inept and incompetent these buffoons really were, and how they stumbled into success and fame. Our first story is about who these cranks were in the first place, the second about how they were utter failures in the new world and the third about King Phillips’ War, the bloodiest war fought on American soil before the Civil War, and how almost nobody has ever heard of it.

Part I: The Pilgrims. Who the F**k Were They?

Part II: The Pilgrims Fail Upward

Part III: Native Americans Strike Back: King Phillips’ War

So while you’re enjoying that turkey and pumpkin pie, watching some football and getting ready for those Black Friday deals, sit back, relax, and rest assured knowing you are much smarter than most everyone who came across on the Mayflower. Let’s begin.

Part II: The Pilgrims Fail Upwards…

In our first post this week, we talk about how the initial group of Puritans eventually made it over to the New World, ending up over 1500 miles from where they were intending to go. They landed just off Plymouth Rock, and that is where our next story begins….

So the Pilgrims make it to Cape Cod, and immediately go scouting for advantageous places to build the colony. On November 15, Captain Myles Standish led a party of 16 men on an exploratory mission, during which they disturbed an Indian grave and located a buried cache of Indian corn. Thirty-four men went on the second expidition, but the expedition was beset by bad weather; the only result was that they found an Indian burial ground and corn that had been intended for the dead, taking the corn for future planting. A third expedition along Cape Cod left on December 6; it resulted in a skirmish with Indians known as the "First Encounter" near Eastham, Massachusetts. The colonists decided to look elsewhere, having failed to secure a proper site for their settlement, and fearing that they had angered the Indians by taking their corn and firing upon them. The Mayflower left Provincetown Harbor and set sail for Plymouth Harbor. The irony being in that if they had just traveled north a wee bit they would have landed in an area much more hospitable, with the Charles River for water, deep water ports and many hills for defensive positions. Alas, Boston would have to wait for another time to be founded.

The Mayflower dropped anchor in Plymouth Harbor on December 16 and spent three days looking for a settlement site. They rejected several sites, including one on Clark's Island and another at the mouth of the Jones River, in favor of the site of a recently abandoned settlement which had been occupied by the Patuxet tribe. The location was chosen largely for its defensive position. The settlement would be centered on two hills: Cole's Hill, where the village would be built, and Fort Hill, where a defensive cannon would be stationed. Also important in choosing the site was the fact that the prior villagers had cleared much of the land, making agriculture relatively easy. Fresh water for the colony was provided by Town Brook and Billington Sea. There are no contemporaneous accounts to verify the legend, but Plymouth Rock is often hailed as the point where the colonists first set foot on their new homeland.

On December 21, 1620, the first landing party arrived at the site of Plymouth. Plans to build houses, however, were delayed by bad weather until December 23. As the building progressed, 20 men always remained ashore for security purposes while the rest of the work crews returned each night to the Mayflower. During the winter, the Mayflower colonists suffered greatly from lack of shelter, diseases such as scurvy, and general conditions on board ship. Many of the men were too infirm to work; 45 out of 102 pilgrims died and were buried on Cole's Hill. Thus, only seven residences and four common houses were constructed during the first winter out of a planned. By the end of January, enough of the settlement had been built to begin unloading provisions from the Mayflower.

On March 16, 1621, the first formal contact occurred with the Indians. Samoset was an Abenaki sagamore who was originally from Pemaquid Point in Maine. He had learned some English from fishermen and trappers in Maine, and he walked boldly into the midst of the settlement and proclaimed, "Welcome, Englishmen!" They also learned that an important leader of the region was Wampanoag Indian chief Massasoit, and they learned about Squanto. Squanto had spent time in Europe1 and spoke English quite well. Samoset spent the night in Plymouth and agreed to arrange a meeting with some of Massasoit's men.

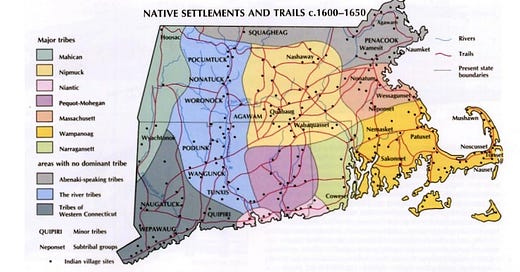

At this point, its important to understand there were dozens of local tribes in the area, and they were not all on friendly terms with one another. The largest was the Naragansett, which many of the other tribes feared. Massasoit looked at the Pilgrims as not too bright; they had created a colony in an area subject to many of the harsh weather elements and with no means of hunting or food gathering that didn’t infringe on the various tribes. He thought they would die soon after arriving.

Samoset returned to Plymouth on March 22 with a delegation from Massasoit that included Squanto; Massasoit joined them shortly after, and he and Governor Carver established a formal treaty of peace after exchanging gifts. This treaty ensured that each people would not bring harm to the other, that Massasoit would send his allies to make peaceful negotiations with Plymouth, and that they would come to each other's aid in a time of war. This was important to Massassoit since he saw the Naragansett as the bigger threat. As promised by Massasoit, numerous Natives arrived at Plymouth throughout the middle of 1621 with pledges of peace. On July 2, a party of Pilgrims led by Edward Winslow (who later became the chief diplomat of the colony) set out to continue negotiations with the chief. After meals and an exchange of gifts, Massasoit agreed to an exclusive trading pact with the Plymouth colonists. Squanto remained behind and traveled throughout the area to establish trading relations with several tribes.

During their dealings, the Pilgrims learned of troubles that Massasoit was experiencing. Massasoit, Squanto, and several other Wampanoags had been captured by Corbitant, sachem of the Narragansett tribe. A party of ten men under the leadership of Myles Standish set out to find and execute Corbitant. While hunting for him, they learned that Squanto had escaped and Massasoit was back in power. Standish and his men had injured several Native Americans, so the colonists offered them medical attention in Plymouth. They had failed to capture Corbitant, but the show of force by Standish had garnered respect for the Pilgrims and, as a result, nine of the most powerful sachems in the area signed a treaty in September, pledging their loyalty to King James and securing peace for the Pilgrims.

So for that first year, the colonists made skeptical allies with the local tribes, which was necessary for their own survival. They used their muskets to help enforce and scare rivals into peace treaties with the colonists to help ensure security. Lastly, they began trade, mostly fur trade, with the native tribes to help procure provisions and supplies from back in England. Things seemed to be picking up for these nitwits in Plymouth. By October/November, they had enough in their stores to last the coming winter, and decided to throw a little party. Of the 120 that originally set out from England for the New World, only about 50 remained. Knowing that half the group died the previous winter and knowing snow was right around the corner, and that the Natives all thought they would die in the winter anyway, why not go out with a nice little bash? You may not live to see another one after all.

In November 1621, the pilgrims celebrated a feast of thanksgiving (or really a typical harvest feast) which became known three centuries later as "The First Thanksgiving". The feast was probably held in early October 1621 and was celebrated by the 53 surviving Pilgrims, along with Massasoit and 90 of his men. Three contemporaneous accounts of the event survive: Of Plymouth Plantation by William Bradford, Mourt's Relation probably written by Edward Winslow, and New England's Memorial by Plymouth Colony Secretary (and Bradford's nephew) Capt. Nathaniel Morton. The celebration lasted three days and featured a feast which included numerous types of waterfowl, wild turkeys, and fish procured by the colonists, and five deer brought by the Wampanoags.

There’s this image of it being this bucolic, friendly, let’s part with our friends kind of thing. According to the accounts though, it was more a constant coming and going with good food than a party. Still, the image pertains. Its a good feeling kind of image. The thing is though that it’s usually depicted of the Pilgrims being benevolent and sharing with the Native Americans who came to the feast. In reality, the Wampanoags brought most of the food and the Pilgrims would all be dead if it weren’t for the Native Americans; it was more a political “Let’s make good neighbors so we don’t die” kind of thing. If there is one thing America is good at, it’s that. I mean, it could have just as easily looked more like this…

It is a strange thing that of those 53 Plymouth colonists who survived that first year in Plymouth, there are about 35 million descendants.2 That amounts to roughly 1 in 10 Americans. When people talk about how the Pilgrims kind of founded America, this is the context of which they are talking. Jamestown would eventually fail and no other early colony has that kind of legacy that Plymouth does. Chances are that if you are related to someone who was in upstate New York or Massachusetts in the late 1600 or early 1700’s, its a good chance that you are related to someone who came over on the Mayflower, prolific propagators as they were.

Good times couldn’t last forever though, and as things often went for the colonists, things would eventually hit a really huge snag. Massassoit would convert to Christianity after the Plymouth colonists save his life with some medicine.3 He would name two of his son’s Alexander and Phillip and continue to rule his tribe in the area for another fifty years. Phillip never really liked the colonists all that much and when Massassoit eventually died, well, things got a little out of hand. We’ll save that though for part III of our Thanksgiving week bonanza.

In the meantime, grab some seconds of pumpkin pie because shit’s about to get real here….

Squanto disliked the Pilgrims but was not trusted by the leaders of the various tribes either. Squanto had been abducted in 1614 by English explorer Thomas Hunt and had spent five years in Europe, first as a slave for a group of Spanish monks, then as a freeman in England. He had returned to New England in 1619, acting as a guide to explorer Capt. Robert Gorges, but Massasoit and his men had massacred the crew of the ship and had taken Squanto.

The Mayflower Society

It is suspected that the chief was suffering from symptoms similar to gout.